The Grand Old Man of Penang – Yeap Chor Ee and the King’s Chinese

Published on June 18, 2020 | by gerakbudaya.com

On Lebuh Penang in George Town, Penang stands the House of Yeap Chor Ee, a museum to the life and work of the “Grand Old Man” of Penang.

As a recently published book on Yeap Chor Ee recounts whilst he arrived in Penang in the 1880s a penniless migrant from China, he ended his life as the only Straits Chinese to found a own bank on his own dime, a rags to riches tale which situates Penang as a thriving port town.

Today the former premises of Bank Bin Han Lee on 43 Beach Street houses a branch of CIMB Bank, a legacy of the bank consolidation exercise Malaysia undertook after the 1997 financial crisis, an exercise which saw many of the smaller Straits Chinese banks consolidated into bigger banking conglomerations.

This marked the end of an era of many of the Chinese financial institutions which had been fostered within the colonial economy of British Malaya. Yet whilst many of these institutions have now been absorbed, their legacy and the legacy of their founders lives on in the landscape of Malaysian life.

One such example would be the building that from the 1930s Chor Ee would call home. Homestead, a mansion built by architectural firm Stark & McNeill for another prominent Chinese businessman of Penang, Lim Mah Chye, who sold it to Chor Ee in the 1930s at a time when as everyone else’s fortunes were in decline, Chor Ee’s were on the rise.

After his stint as a barber, Chor Ee’s entry into the business world in Penang was through the founding of his own provisions shop, Chop Ban Hin Lee, at the age of 23. Initially serving as a middleman between British importing houses and local consumers, Chor Ee made his fortune participating in the commodity booms of Southeast Asia in the early 20th century, moving beyond dependence on the British to create his own transnational business network operating at all levels of the supply chain, from retailing to producing.

Beginning as a middle-man for Chinese sugar and rubber plantations in Province Wellesley, he soon became an importer of the sugar of Oei Tiong Ham the “Sugar King of Java” and the richest man in the Far East during the early years of the 20th century.

Yeap Chor Ee would buy up locally produced sugar, forward it to Oei Tiong Ham’s refineries in the Dutch Indies and would sell the refined sugar in Malaya at a good profit. As the story goes, Tiong Ham surprised by Chor Ee’s growing dominance in the Malayan market held off charging Chor Ee for the refined sugar, assuming that the $2 million bill would bankrupt him, and allow Tiong Ham to gain a strong foothold in the market. But Yeap Chor Ee ever the thrifty businessman, had the money and soon paid up.

Chor Ee was also able to take part in the booming rice industry in the region, showing how his horizon went beyond Malaya. At a time when global demand for rice was rising, and Malaya was importing rice to feed its growing work force, Chor Ee established the Hin Bee Company Limited in Rangoon and set up rice mills in the town of Wakema, in the Irrawaddy Delta, Burma, one of the largest producers of rice in the world, to import rice into Malaya.

He was also a successful speculator. When the rubber boom began to hit Malaya in the 1910s he successfully bought up large tracts of land on the mainland. Meanwhile when the price of tin slumped as the Great Depression began to bite, he bought cheap only to sell it for a great profit in the 1930s. Providing a significant amount of money that contributed towards his founding of Bank Ban Hin Lee in the 1930s.

Yet beyond business, Chor Ee’s life was also the story of an emerging luxury economy in Penang. Aside from the buildings he erected Chor Ee was also purchasing European cars, cinema projectors and high fashion, blending the Chinese culture he remained loyal to with the new trends emerging out of Europe and America, a combination which led him to be considered a “Kings Chinese”, a term usually reserved for the Anglicised Straits Chinese.

Chor Ee didn’t speak English until his death, and hadn’t, like figures such as Lim Boon Keng and the Straits Chinese British Association, politically oriented himself towards the British Empire. Yeap Chor Ee was more interested in business. Yet for his philanthropy and donations to local institutions, he was to be considered for an award from the British, organised by Tan Cheng Lock. Yet with the death of Henry Gurney and the death of Yeap Chor Ee the award wasn’t to come to pass. His legacy lives on however in the buildings of Penang, which offer an insight into the rich history the city has to offer.

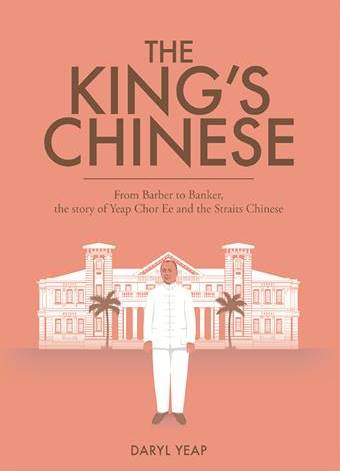

To find out more about Yeap Chor Ee visit the House of Yeap Chor Ee on Jalan Penang, George Town or purchase The King’s Chinese through Gerakbudaya.